Author: Claire Wayner ’22

Stuck at home and tired of your garbage can getting stinky? A full 22% of your trash (or more) is likely food, and food waste doesn’t smell too great after a couple of days. There’s an easy and environmentally friendly solution to the odor – start composting!

By breaking down the food in combination with leaves and water, the process yields a rich, nutrient-filled soil additive called compost that can be used in your home garden beds or gifted to your neighbors (here is an article on the benefits of compost for your garden). Composting at home is really easy to start up and doesn’t require a ton of resources. My family has been composting since I was in middle school, and since then, we’ve learned a lot of helpful tips which I’ll share with you below.

During the day, we collect our food scraps indoors in an old yogurt container in the fridge to prevent it from smelling up our kitchen counter. We then empty the scraps into our outdoor composter whenever the indoor container is full. Our outdoor composter is a tumbling, elevated version which we keep in our backyard. It’s definitely worth the investment to buy a model like the one we have because it keeps food scraps contained and elevated (to prevent us from attracting unwanted pests like rats, as we live in a city) and also makes it easier to regularly turn the compost (moving the scraps around is important to promote breakdown and aeration). You don’t need a shiny new container to start composting, however. In a pinch, you can build your own out of anything from milk crates to recycled lumber.

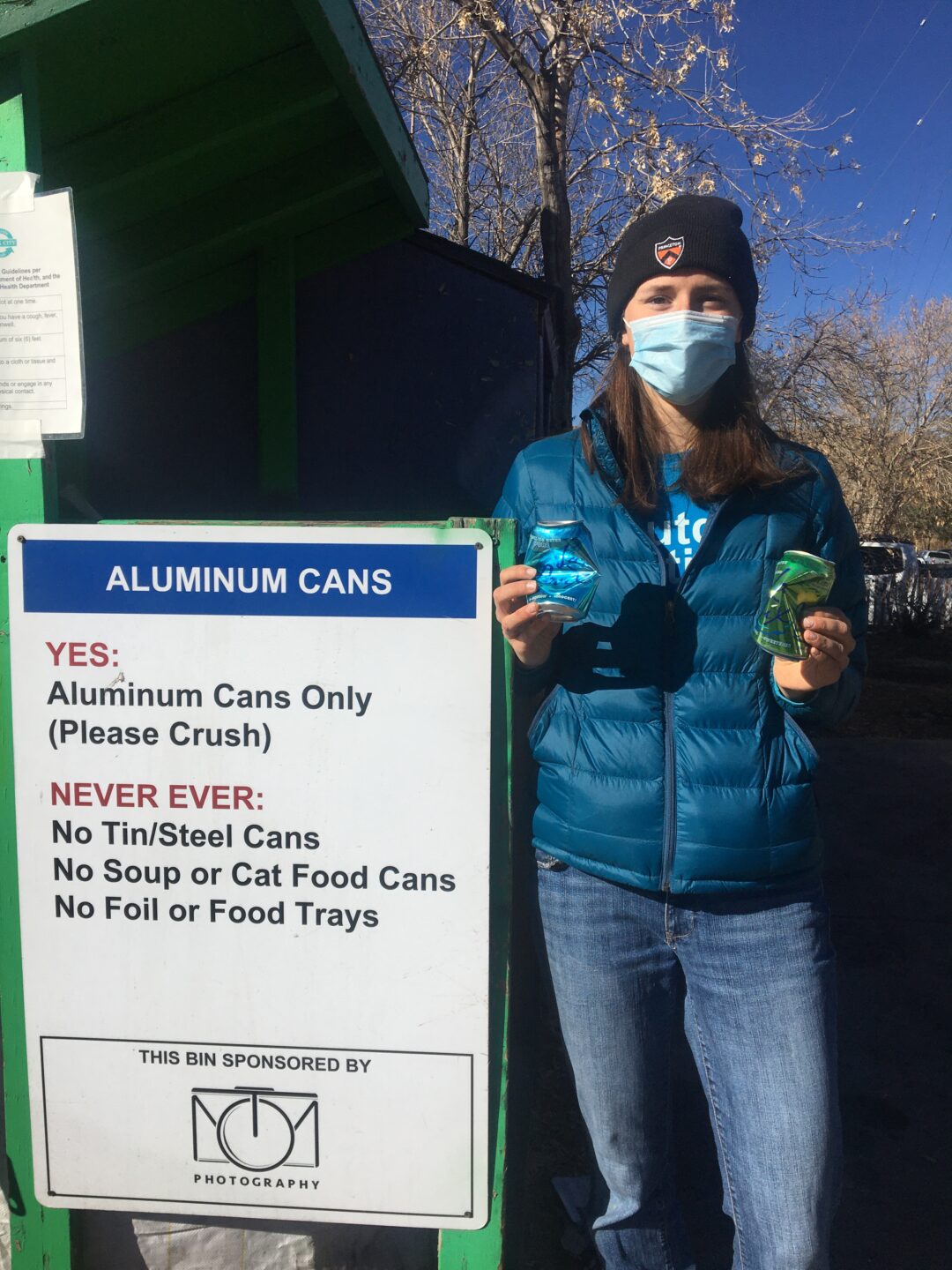

Photo Credits: Claire Wayner

Keep in mind that you can’t compost all of your food scraps at home – things like dairy, meat, prepared foods/dishes, and disposables marked as “compostable” should stay out of your home compost, as they won’t break down unless put in a more industrialized composting environment like Princeton’s S.C.R.A.P. Lab. Stick to things like fruit and vegetable scraps, eggshells, coffee grounds, or clippings from your yard (raked leaves in the fall are great!). Try to get your ratio of “greens” (e.g., grass clippings, fruit and vegetable scraps) to “browns” (e.g., leaves, eggshells) right.

There are plenty of tutorials online on how to get started (check out this one from NPR). If you live in a dense city and can’t easily set up a compost bin, there are always countertop composters for apartments, or you could check to see if your municipality offers curbside composting pickup (ShareWaste has a great directory of where to drop off your compost if you can’t use it in your home).

Photo Credits: Claire Wayner

By starting to compost, you can make a big difference. Most greenhouse gas emissions from landfills come from the breakdown of food. Composting can reduce these greenhouse gas emissions and give us a usable product at the end of it.