Author: Jayla Cornelius ’23

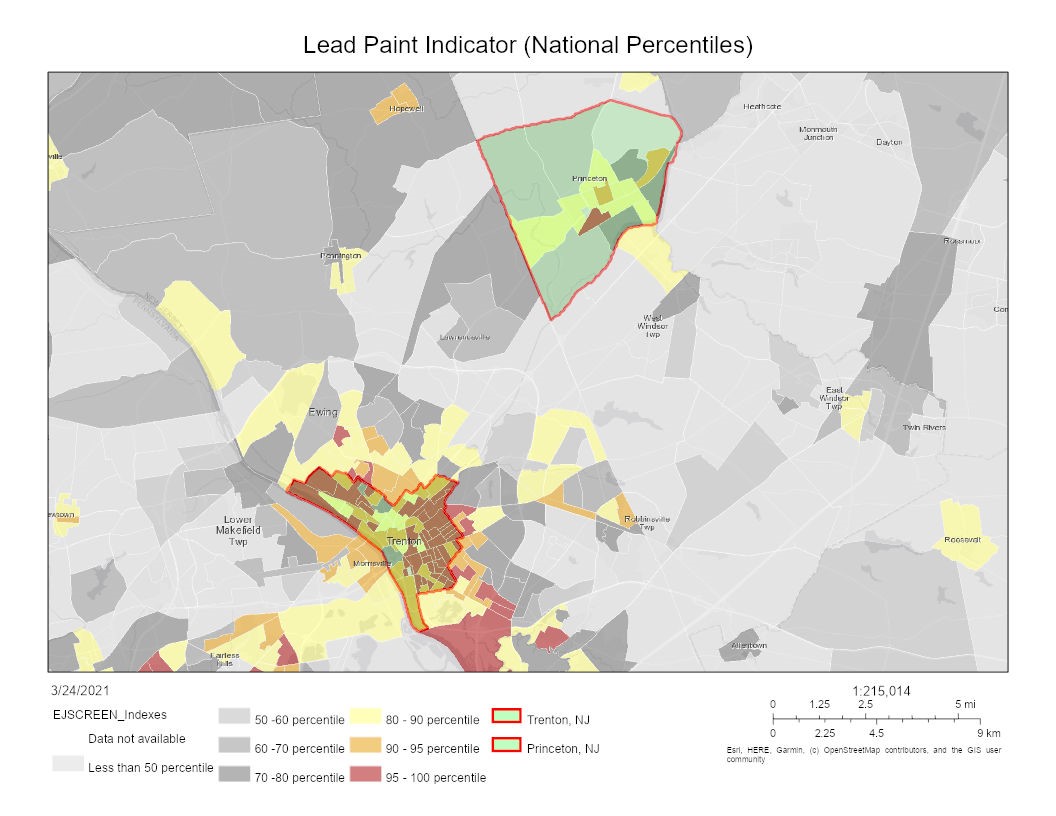

Crumbling pipes and tainted water have continued to plague communities of color across the nation. The subsequent lead poisoning that comes with the corrosion of these lead pipes is at the forefront of the conversation around environmental justice issues.

In places like Milwaukee, Wisconsin, we see the detrimental effects of this lead poisoning. 2018 Wisconsin blood testing data for children under the age of six were collected into a report by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. The results are alarming; in certain jurisdictions, the percent of children with more than 5 mcg/dL of lead in their blood is as high as 9.5%. This proves to be a significant anomaly from the expected percentage when we look at the many other jurisdictions in Wisconsin with less than 4%.

This disproportionate variation between the lead poisoning of children in different jurisdictions can, of course, have many contributing factors not associated with environmental racism. However, a 2019 study done at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee reported that “the risk of elevated childhood blood lead levels is greatest in majority non-White Milwaukee County neighborhoods with high poverty and low homeownership.” The Milwaukee Common Council is now trying to address the obvious unfair circumstances that put communities of color in a more vulnerable position when it comes to lead exposure. “Not only do we have inequities for risk for children in Milwaukee, but that’s been compounded by a lack of access to services for children whose blood lead levels fall between 5 µg/dL and 20 µg/dL,” Hellen Meier, associate professor at UWM, says. The Coalition on Lead Emergency’s (COLE) chair, Rev. Dennis Jacobsen, says that more efforts are being made to create programs that certify that properties are lead-safe before they are rented out to people, particularly in low-income or BIPOC neighborhoods.

How harmful is lead actually?

Lead is a very harmful poison that has the ability to affect almost every organ in a child’s body. Even when blood lead levels are at the lowest measurable values, the toxin can still compromise the child’s reproductive, neurological, and cardiovascular systems. Depending on the amount and duration of exposure, lead can cause “gastrointestinal disturbances”, such as anorexia, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Lead also has concerning effects on a child’s neurological development. Researchers say that, globally, lead accounts for approximately 10 percent of intellectual disability cases that are categorized to have an unknown origin. A 2009 study also estimated that up to one in four cases of ADHD amongst 8 to 15-year-old children may be attributed to lead poisoning. These statistics make the regulation and mitigation of lead exposure even more pertinent as it shows the serious impact lead has on the physical and neurological development of young children all over the world.

How are we working towards mitigating this issue?

The long-term solution to ending this harmful exposure to lead is to replace the lead pipes that are corroding and causing this neurotoxin to be digested in people’s drinking water. However, the dismantling and replacement of this lead-based pipeline infrastructure would take years and a large budget. The more feasible option is to figure out how much lead is actually coming into people’s homes through tap water so we can find more effective ways to mitigate this issue. This past October of 2020, researchers from the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis officially came up with a solution using acid. Senior Elizabeth Johnson and graduate student Weiyi Pan tried many different methods but eventually discovered that slowly passing an acidic solution through a commercial filter would free 100% of the lead captured by that filter. They have come up with the most accurate method to date that would help researchers collect data to see just how much lead would be potentially entering households.

In the conclusion of their research report, the scientists stated that “additional experiments are needed regarding different tap water conditions and PbO2 solids.” They encouraged residents to send their used filters to laboratories so more in-depth data could be taken in a variety of conditions. These field studies would help researchers and utilities select reliable methods for analyzing Pb exposure and corrosion control effectiveness in the pipeline infrastructure. With this new method, we could potentially move one step closer to mitigating the lead exposure amongst young children and lessen the harmful effects it has on their development.

To get involved and for more information visit:

http://coalitiononleademergency.org/