Author: Jayla Cornelius ’23

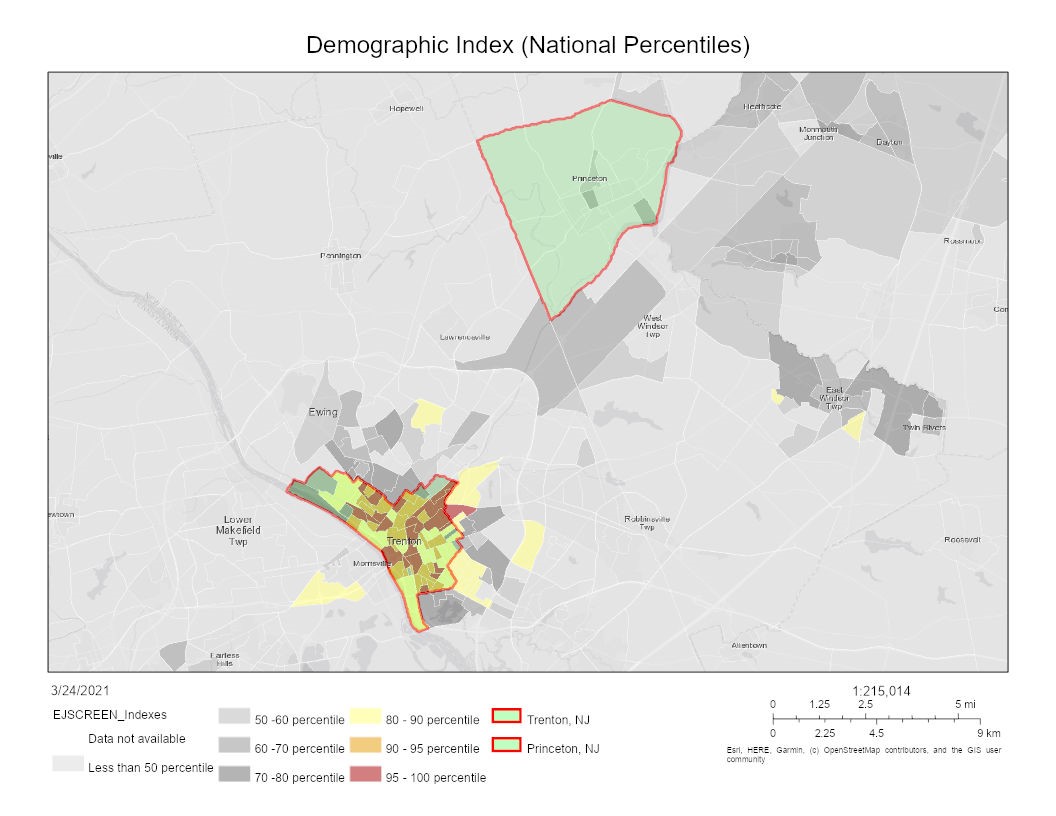

The textbook definition of redlining is “the discriminatory practice of denying services (typically financial) to residents of certain areas based on their race or ethnicity.” Very commonly in the world of mortgage lending practices and homeownership, people of color are denied loans and renting contracts because of preexisting stereotypes amongst realtors that often deem them as incapable of keeping up with the property and/or making timely payments. This is, at least, what they claimed was their reason behind denying millions of African Americans access to certain neighborhoods across the country. But, as we dig deeper, we can uncover a long history of discriminatory practices that have strategically and effectively pushed Black Americans into certain areas, usually more decrepit ones, and creating a distinctive “red line.”

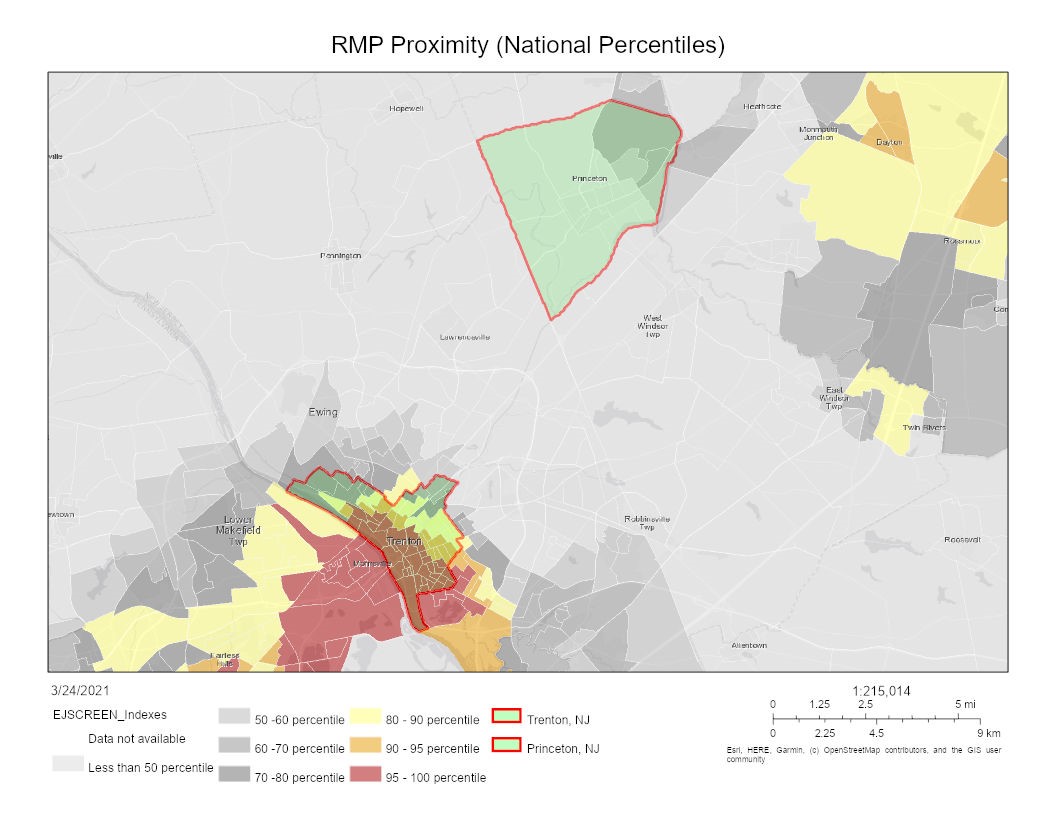

If we were to dive into historic records and search for obvious instances of redlining, we would have a pretty unsuccessful turnout. The reason why this modern form of segregation has been able to persist for so long is because of its slightly elusive nature. Minority neighborhoods were stigmatized by being labeled as “High Risk” or “Hazardous” from supposedly credible sources like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) that has created residential security maps of America’s major cities. Appraisers, loan officers, and real estate professionals then use this as evidence to funnel white homeowners into the more affluent, better-kept neighborhoods. Notably, this strategy not only works to keep white homeowners away from minority neighborhoods, but as you begin to associate certain areas with hazard, you begin to label the people as hazardous also.

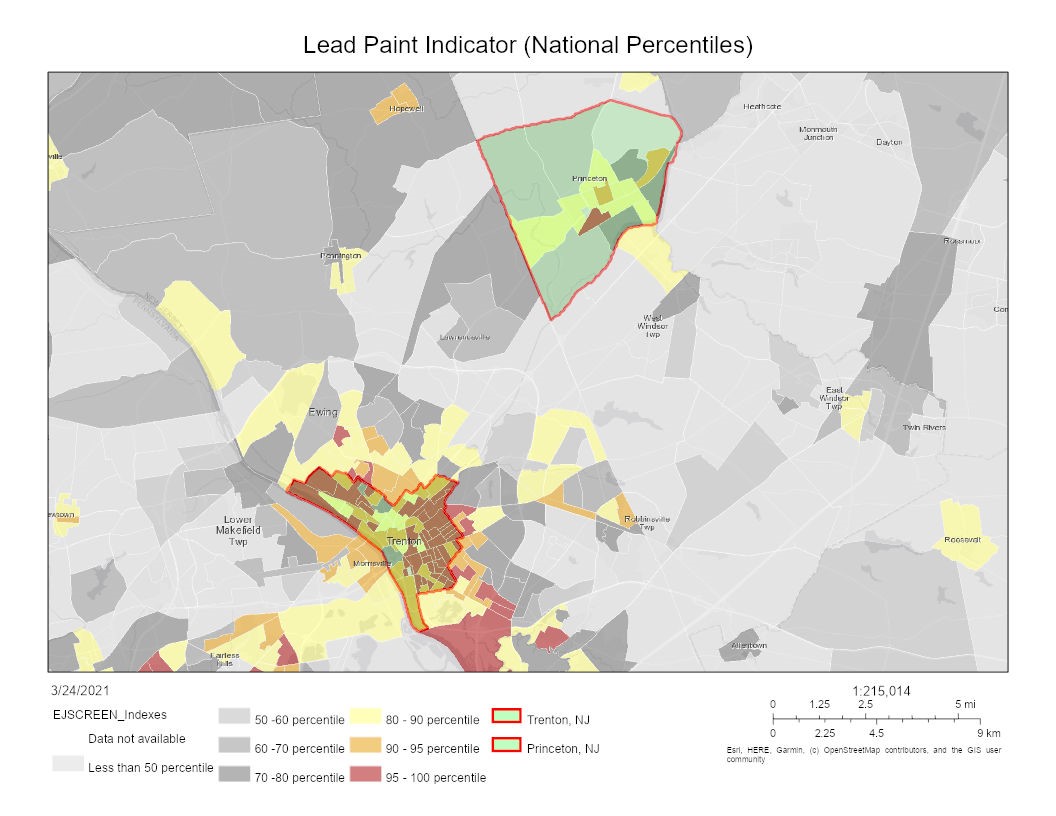

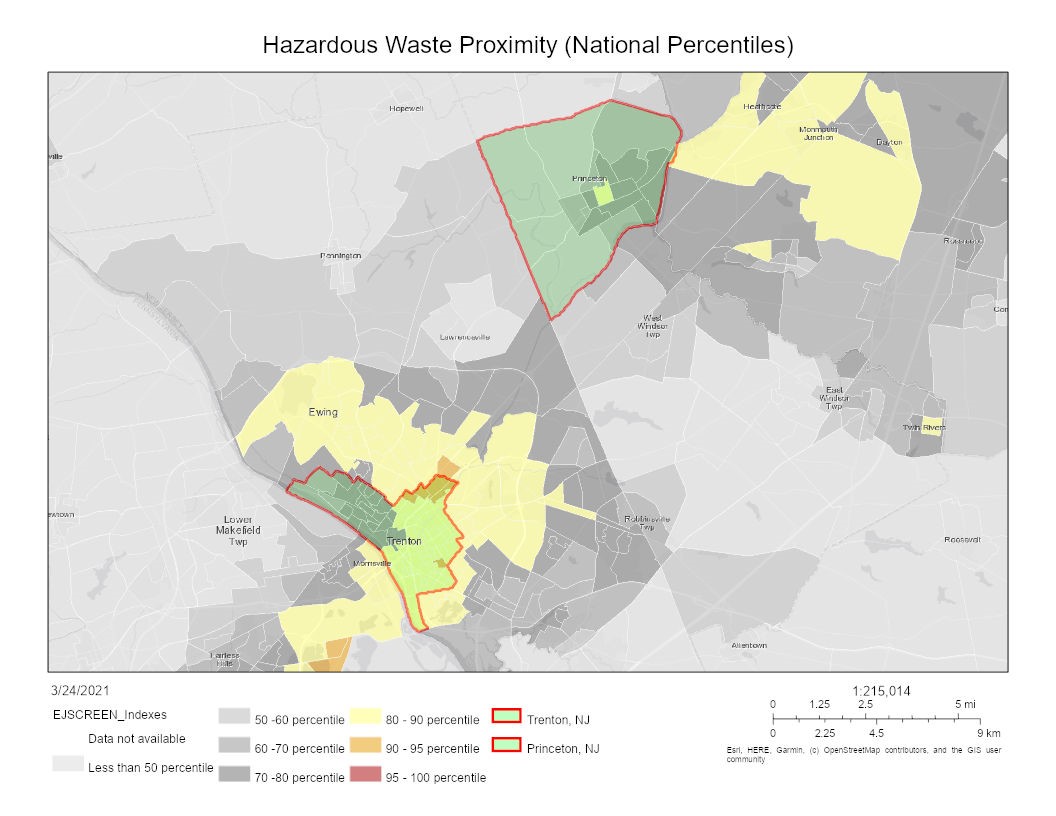

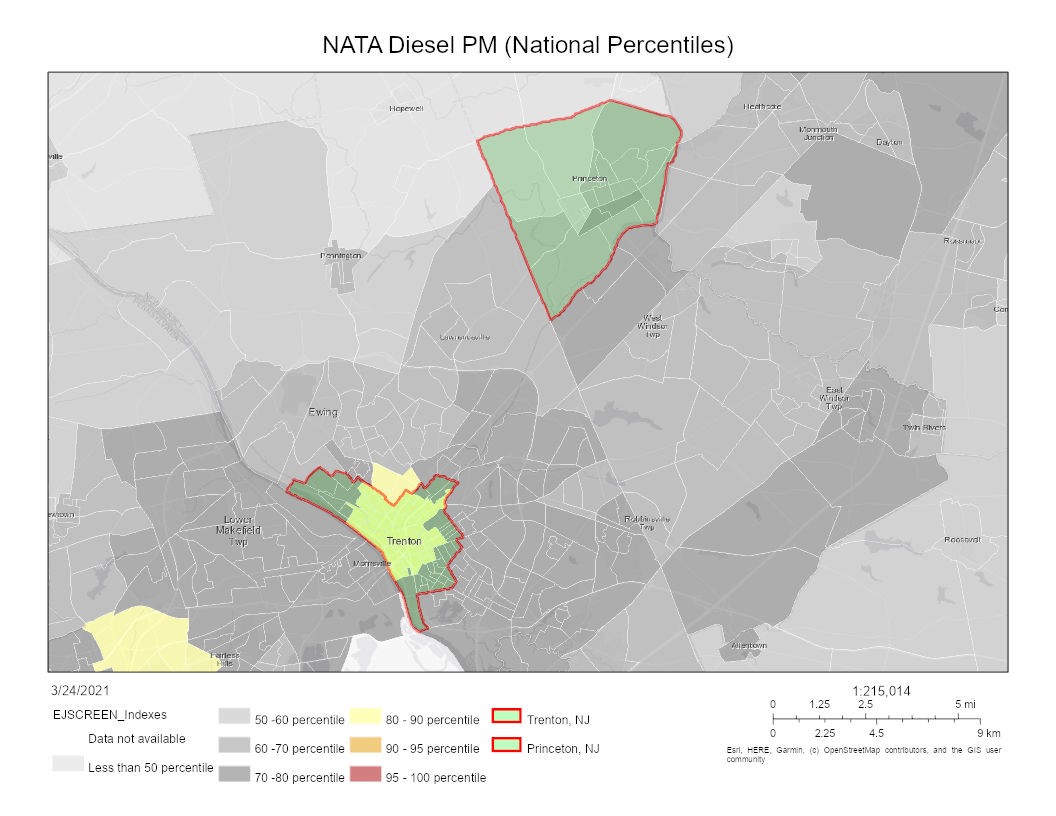

Because the rabbit hole of bad housing practices is never-ending, I will now focus the rest of this article on specific instances where black women have been such targets of these bad housing practices. Since the 1970s, many real estate agents have taken advantage of the financial barriers and hardships that Black women endure to sell them mortgages on homes with inhabitable conditions. Yolanda, for example, is a homeowner in New Orleans’ predominantly Black 7th Ward who was backed into a corner and forced into a high-interest loan. The area is riddled with constant noise from the nearby interstate and higher rates of pollution than the adjacent neighborhoods. Many homes in this area are ladened with leaky roofs, broken pipes, and numerous other health and safety code violations. Climate change has continued to exacerbate this issue as increased rainfall and extreme temperatures will cause things like mold and mildew to fester in already unclean environments. Doris, a homeowner in Chicago, notes that “…so much water came in the basement that my washer and dryer was floating up on the water.”

This practice of selling homes to Black women that are in need of obvious repair is just one way that redlining can expose this demographic to unsafe environmental conditions. Things such as rotten wood and improper ventilation systems can cause various respiratory diseases and related health issues. The government has acknowledged their responsibility to help people suffering from housing discrimination but even this aid is “uneven and hard to obtain.” Through these findings and interviews from local residents such as Yolanda and Doris, we can recognize the disrepair of homes in certain areas as environmental racism that must be addressed in our environmental justice efforts.

This article’s main purpose is not to establish redlining as this new, harmful phenomenon. We have unequivocal proof that it has existed for decades. Our purpose is to keep this issue at the forefront of our minds as we continue the conversation around environmental justice issues. At face value, redlining may not seem to fit into the category of environmental injustices but if we continue putting Black women in homes with bad piping and non-potable water, it becomes an environmental issue. Instances such as the ones described above continue to put the health and safety of communities all over the country at an avoidable risk. Laws such as the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act that sought to combat redlining are still being maneuvered around in more discrete ways. While these elusive behaviors make our environmental justice efforts more difficult, the goal of creating equitable environments for all still remains possible. By engaging with this environmental justice series and keeping this conversation going, you are helping keep this issue at the forefront of this conversation so that, one day, we may all enjoy the feeling of safety and security within our respective communities in Princeton, and beyond.

Sources:

1977 Anti-redlining Law: https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/files/cra-npr-fr-notice-20220505.pdf