Author: Camellia Moors ‘22

When nuclear power is used on a commercial level to produce electricity, one unavoidable byproduct is high-level nuclear waste (HLW) in the form of spent fuel rods. Currently, the only strategy the United States has to manage this waste, which takes thousands of years to decay, is to build a site underground, known as a permanent repository, where the waste can be stored until no longer dangerously radioactive. The only problem with that plan? The U.S. does not have a permanent repository built, and the only substantive plans for a storage site in Nevada have been plagued by political obstacles and local opposition.

For my junior independent work as part of my task force for the School of Public and International Affairs, I analyzed the current state of repository policy, why climate change might make the need to figure out a permanent solution even more urgent, and what policy changes could be implemented to streamline federal decision making on nuclear waste. My paper is titled “Commercial High-Level Nuclear Waste in the United States: Overcoming Political Barriers to Short- and Long-Term Storage Solutions.” I chose to examine nuclear waste because with climate change growing worse, there are a lot of questions about whether nuclear power, as an emissions-free electricity source, should be part of a renewable energy transition; these questions, however, tend to ignore existing issues of nuclear waste, which will only grow if nuclear power increases. I also was really interested in the idea of bringing climate change directly into this debate.

On-Site Waste Storage, Political Obstacles, and Climate Change

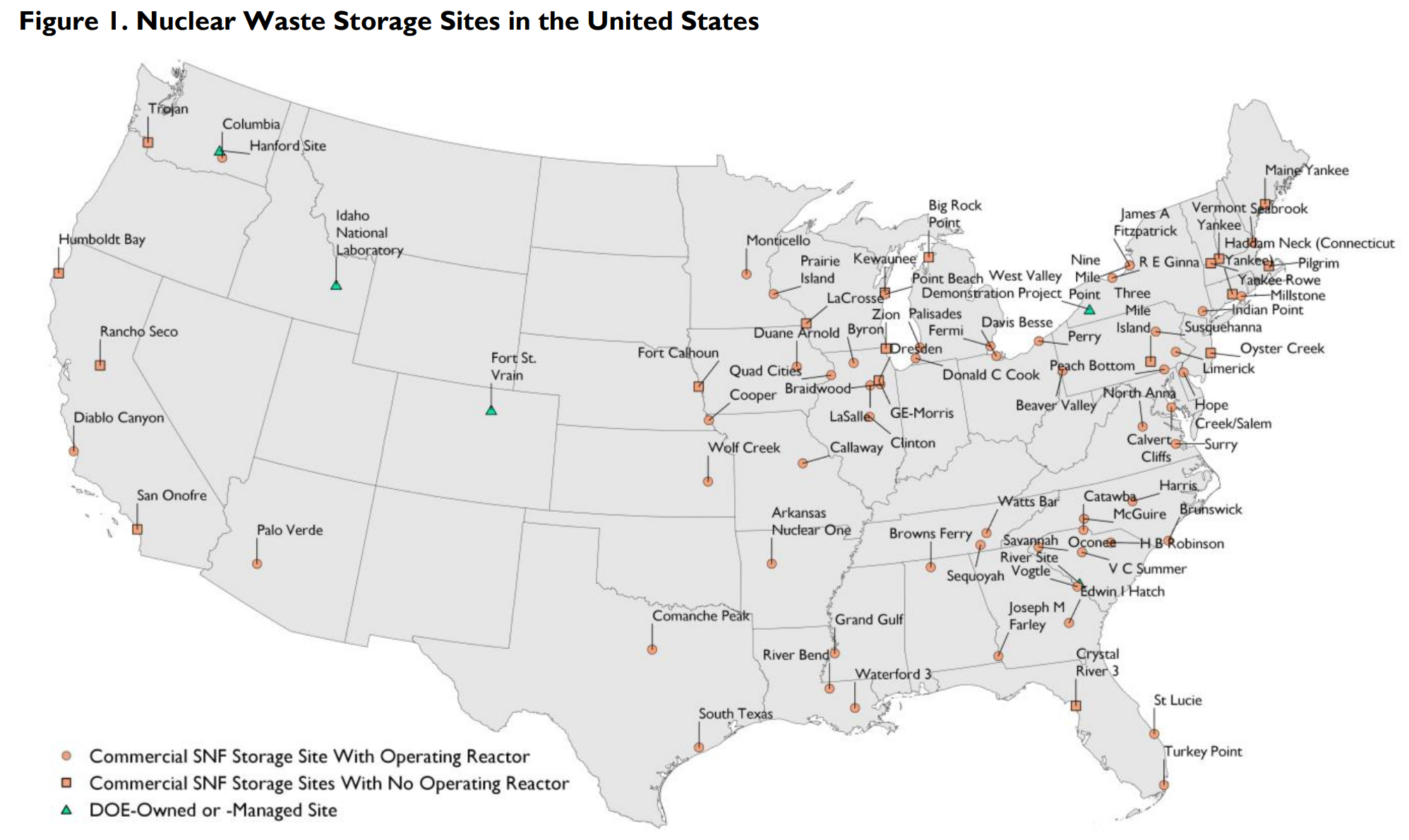

Due to the lack of a permanent repository, America’s 80,000 metric tons of domestic HLW from commercial nuclear power (CNP) is temporarily stored on-site at nuclear power plants, as the map above shows. The operation of existing nuclear power plants increases that HLW by 2,000 metric tons/year. In my analysis of the causes and consequences of this on-site storage dependence, I found:

- The federal government is obligated to build and manage a national permanent repository under the Nuclear Waste Policy Act (NWPA) of 1982;

- Utility companies that produce nuclear energy have been forced to manage on-site HLW, leading to lawsuits against the Department of Energy (DOE) that have resulted in $8 billion worth of payouts to utilities;

- Many temporary storage sites are financially unsustainable, threatened by the limited lifespan of temporary facilities, and at risk of flooding from climate change-driven sea level rise;

- Yucca Mountain, the only possible repository location currently capable of being licensed under the NWPA, is not in operation mostly due to political opposition rather than technical obstacles; and

- Funding mechanisms for the Nuclear Waste Fund (NWF) hinder the DOE’s ability to implement short-term solutions made necessary by the above financial and environmental concerns and which would reduce some of the urgency to build a permanent repository.

In other words, my analysis found that the United States’ nuclear waste problem will grow more expensive, unsafe, and dire the longer a solution is delayed.

Fixing the Problem

In light of my findings, I made a list of policy-based recommendations which could reduce the current strain on temporary on-site storage in the short term and/or bring the United States closer to constructing and operating a permanent repository in the long term:

- A working fund for DOE and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) repository siting/licensing efforts (i.e., finding and approving new feasible repository locations) should be established outside of the NWF. Fees on nuclear power producers should be reinstated and added to this fund.

- The NWPA should be amended to allow for the use of federal and private consolidated interim storage facilities (CISFs) to fulfill the growing need to move HLW away from on-site storage.

- A consent-based repository siting approach should replace the existing process to overcome political hurdles. Yucca Mountain should be reevaluated under this new siting system.

- HLW that is most threatened by sea level rise and/or is most expensive to keep in temporary storage should be prioritized for transportation into CISFs and/or repositories, once available.

America’s nuclear waste storage problem is a complicated one, but that is all the more reason why it cannot continue to be ignored. Questions of nuclear power’s role in America’s energy transition to confront climate change cannot be fully and accurately answered until short- and long-term HLW storage solutions are implemented.