Author: Wesley Wiggins ‘21

Sea-level rise is a local phenomenon just as much as it is a global one. While melting ice sheets, mountain glaciers, and the expansion of the oceans all have far-reaching impacts, every coastline will experience sea-level rise differently. I focused my senior independent work for the Department of Geosciences on the effects of sea-level rise in one location in particular: the Chesapeake Bay.

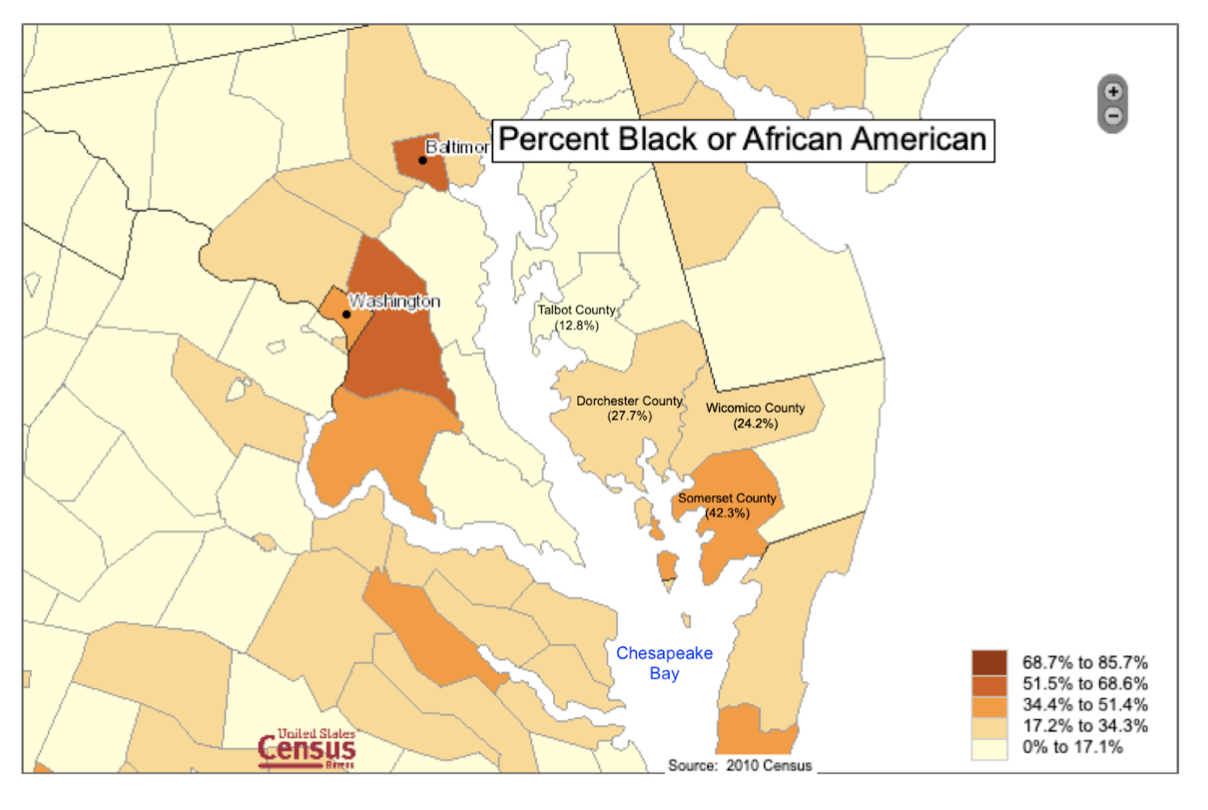

In my senior thesis, titled Sea-Level Rise on the Eastern Shore of Maryland: Vulnerability, Adaptation, Environmental Justice, I analyzed sea level rise data in Cambridge, Maryland, and conducted a survey to understand residents’ experience with rising sea-levels and their adaptation preferences. I chose to study the Eastern Shore because it is an area close to my own home in Washington, DC. Having visited the Bay many times, I’ve seen the beauty of the environments and the wonderful residents. The Eastern Shore is home to a large African American population, a group that is particularly vulnerable to the effects of sea-level rise because of a lack of access to resources, lack of representation in decision-making circles, and historical discrimination.

Sea Level Rise Analysis

From an analysis of local sea-level projections until 2100, I found that the sea level may increase by an average value of 88 cm, relative to mean sea level in 2000, if global temperatures rise 2˚C by the end of the century. If global temperatures rise by 5˚C, then the average sea levels may rise by an average of over 140 cm. Additionally, there is around a 36% probability that sea levels will rise by 1 meter or more in a 2˚C scenario and about 75% probability of this in a 5˚C scenario.

For some historical context, Hurricane Isabel made landfall in Maryland on September 19th, 2003 and caused water levels to rise to 1.26 m. This event flooded almost half of Dorchester County, cut off power to 1.4 million Maryland residents, injured 200 people, and even killed 1 person. The current frequency of a 1.26 m water level rise occurring is 1 in 286 years. By 2100, we will see these events amplified by 2000 in a 2˚C warming scenario with 7 events per year, and amplified by over 8500 in a 5˚C warming scenario, with 30 events per year.

Survey of Residents

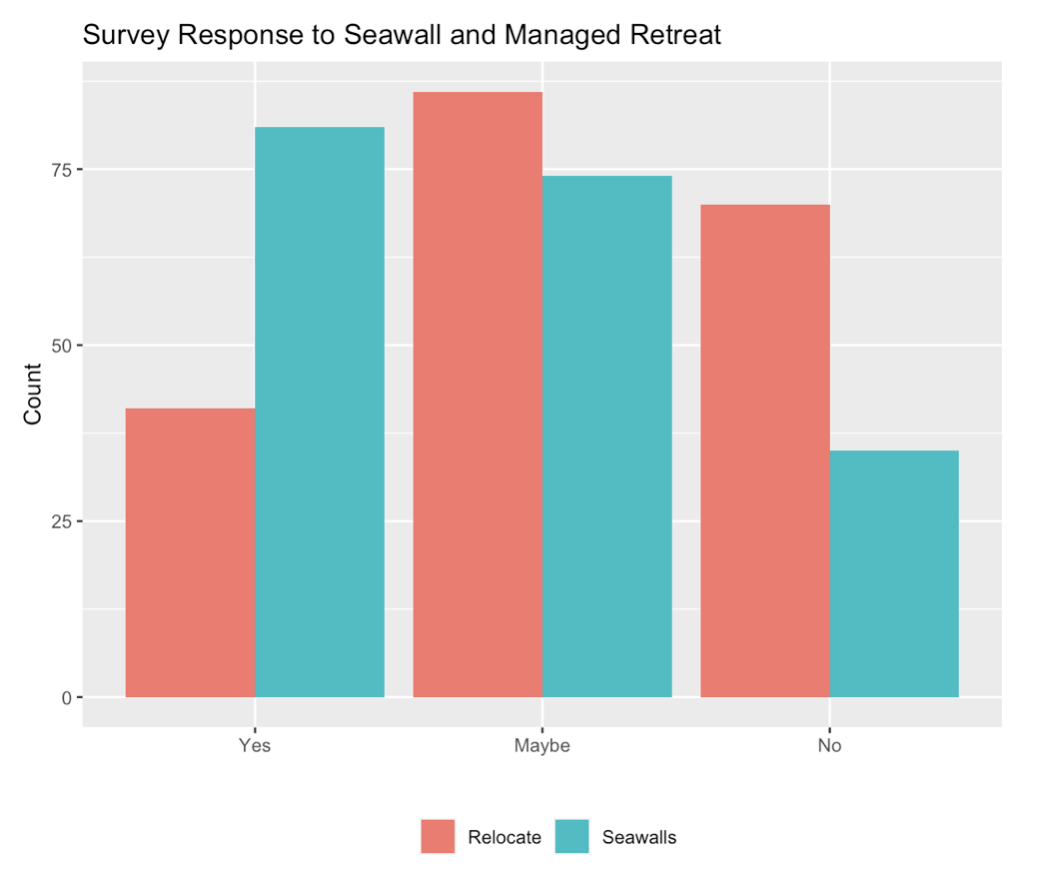

In my survey, I asked if residents would support a seawall, a barrier parallel to the shoreline which defends the coast against sea-level hazards, or would rather a relocation program such as managed retreat. The majority of residents supported a seawall, but had mixed feelings towards relocation, with a most opposed to leaving their homes. Community preservation was a big explanation for supporting seawalls, which many saw as a plausible solution when used with other techniques. Some saw managed retreat as the best option while others saw it as a last resort. Others believed that by relocating their homes, their land would be given to more wealthy individuals, which made them unwilling to move. Residents gave many reasons for taking different positions on adaptation efforts, yet many of them are rarely heard by the groups that make decisions. When the voices of the community are not heard, the people that need the most help could actually end up being more hurt than helped by adaptation efforts.

It is important to remember: How we take action is equally important to or even more important than taking action. The people who make adaptation decisions should change how they operate to accommodate these communities. This could mean increasing the transparency in decision-making process, increasing the consideration of social injustices in long-term adaptation planning, and engaging in participatory planning. Improving these practices can help to decrease the environmental injustices present in the Chesapeake Bay, but we shouldn’t stop there. These practices should be implemented beyond the Chesapeake Bay in order to pursue environmental justice on a global scale.